From Brooklyn To Lakewood — And Now Queens

Recently on Chazaq Torah Talks, we sat down with a rav whose life story reflects the very topic of the night: building communities.

Rav Mansour shared how he was born into the Syrian community at a time when local chinuch infrastructure was still developing. With no established path close to home, he went to yeshivah in Brooklyn—where Rav Avrohom Mandel opened doors for many Syrian boys and helped lay foundations that shaped an entire generation. Those years, he said, were among the greatest of his life. Afterward, he spent roughly 12 years in Lakewood, absorbing the power of Torah-driven community life.

That journey—Brooklyn, Lakewood, and now the growing phenomenon of Torah in Queens—set the stage for a question many families face today: when moving from Community A to Community B, what should you be looking for?

A Community Is Not A Convenience Store

The rav framed it as a two-part question: what does it mean to be part of a community, and what should you seek when relocating?

He quoted an unforgettable line from Rabbi Avigdor Miller, zt”l, one of his great inspirations. His mother used to take him to Rabbi Miller’s Friday night shiurim, and later, as an eleventh grader, he had the zechut to help set up recording equipment—back when there were no video machines and “taping shiurim” was still revolutionary. Rabbi Miller, he noted, was a true pioneer of the audio era, with recordings dating back to the late 60s and early 70s.

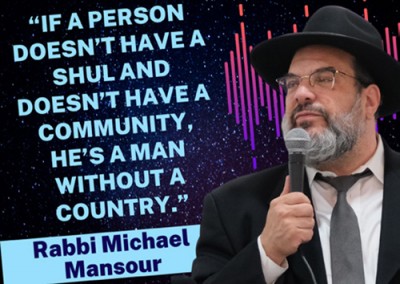

Rabbi Miller once described a man whose “community life” was scattered—one place Friday night, another place Shabbat morning depending on when he woke up, another minyan during the week wherever was convenient. Rabbi Miller’s response was sharp and simple:

If a person doesn’t have a shul and doesn’t have a community, he’s a man without a country.

The rav explained that people often ask, “What can I get from this community?” But to truly belong, you can’t treat a community like a convenience store—where you stop in only when you need something. A real community means giving, showing up, being loyal, and being counted.

A shul, he stressed, is not a social club. A social club is where you come to relax and benefit socially. A shul is meant to be an extension of your life—your second home.

Why It Was Called A Shtiebel

He underscored this idea with a language lesson that carries a whole worldview: in Yiddish, a shtiebel literally means a “little house.” It was designed to feel like your home—daily, steady, dependable—not a place you drop into only when it’s convenient.

He connected this to tefilah as well. Many people experience davening as an “obligation,” something to get through quickly. But the rav argued the opposite: the structure of Jewish community life is built so that you are actually receiving—spiritually, emotionally, and personally—far more than you think you are “paying.”

That’s why, he said, when davening takes “three minutes longer,” people get tense—because they see it as a burden instead of life-giving oxygen.

He brought a story from his years in Boro Park at Rav Wolfson’s shul. Someone asked whether, because he needed to leave early for work, he should daven in a different local shul where tefilah was shorter. Rav Wolfson told him that even if he could only stay for part of davening, it was better to come to his shul and leave early.

Why? Because beyond tefilah, this is my place. This is where I belong.

What A Rav Gives A Community

So what is the gain of real community membership?

He said the answer can be seen in the way children relate to Torah, school, and life. In his own family, the rav explained, his children feel comfortable approaching the rabbi directly with questions—because the rabbi isn’t “a figure,” he’s part of their world.

He described visiting Muncie and watching a prominent maggid shiur interact with people after davening. While adults lined up for “Shabbat shalom,” the rav stopped each child and asked personal questions: How was your week? What are you learning? He knew which grade they were in and what they were holding by.

The children waited for that moment.

He explained why: a smile and recognition from a rabbi can carry a weight children sometimes don’t even receive at home—not because parents don’t care, but because homes can be pressured and stretched. That positive attention becomes fuel. A child can be motivated to learn well all week just to earn that warm glance and a “good Shabbat.”

Small Groups Build Empires

The rav then shared a key strategy from his own experience in building Torah communities—especially among working balabatim.

When Rav Mansour began, the Rosh HaYeshivah started with a small group: about 10 avreichim before Shacharit and 10 after, not one oversized crowd. He admitted that he originally assumed the goal was to build big classes quickly. But he learned something surprising: big classes often produce less growth because you lose individual connection.

Rav Mansour said, “You want to catch too much, you don’t catch anything.”

The model that works is building small, solid groups where people are seen, known, and cared for—until that becomes the foundation of something lasting.

Why Community Protects Our Children

Rav Mansour spoke passionately about today’s challenges with children and explained that community is not just a “nice add-on.” It is protection.

When a child feels part of something—when he knows his parents are loyal to a rav and connected to a shul—the child thinks twice before doing something destructive. Not because he has no struggles, but because he’s attached to a larger identity.

Rav Mansour pointed out that some communities have this built-in: being part of something big creates stability. But in many places today, families are fragmented—davening here, learning there, no deep connection to a rav—and children sense that. When the home isn’t anchored to a community, children are left feeling like individuals floating alone.

Rav Mansour's line was simple, heartfelt, and direct: “Things that come out of the heart go into the heart.”

Torah Must Be A Candy Store

When asked how Torah itself transforms people, he described a common mistake: many treat Torah like “paying dues.”

A person may learn Daf Yomi and feel accomplished—but if it feels like a bill you pay, it won’t change you. Torah, he said, needs to be approached like walking into a candy store—enjoyed, tasted, desired.

Rav Mansour tied this to a broader cultural weakness: our “fast-food mentality.” People don’t sit with anything long enough to develop taste—whether it’s food, relationships, or spiritual life. He gave a striking mashal: if you don’t savor a steak—if you rush it and gulp it down—you walk out with a stomachache and a big bill, but no enjoyment.

Torah requires patience, and patience builds depth. When a person slows down and truly understands—even a sugya that isn’t “practical”—his personality changes. He becomes happier and more alive.

Rav Mansour shared a vivid example from their own community: several men began learning seriously and eventually moved into full-time learning—not even for pay—because the Torah itself became energizing.

The Rav’s Most Important Attribute

Rav Mansour defined the core attribute of a rav as involvement in the nuances of the community—real, individual care.

Rav Mansour illustrated it with a story from his youth. A rav advised him about going to a certain yeshivah—but didn’t stop there. The rav got into the car, drove him to the interview, and sat with him through it. That is leadership: not advice from a distance, but personal responsibility for another Jew’s success.

Rav Mansour added a second example: true leaders notice the boy who can’t afford a trip, and they quietly make sure he gets to go.

Rav Mansour quoted a powerful line: you can’t be a leader without individual attention.

Raising The Bar Changes The Whole Community

The conversation then turned to a major Chazaq priority: getting children out of public school and into Torah environments.

Rav Mansour explained the broader strategy: if you want public school to stop being “an option,” you raise the bar across the community. When Torah learning becomes the norm and standards rise, the entire community moves upward—and families who once saw public school as acceptable begin to feel, “What am I doing?” The shift becomes a domino effect.

Rav Mansour referenced how communities that grew—whether in Flatbush, Mexico, and beyond—often began with one person raising standards. People resisted at first, accusing leaders of becoming “too right-wing,” but over time, the entire community rose higher than it had been before.

Final Message: Judaism Is Not A Burden

Rav Mansour's closing message was sharp and necessary:

Don’t present Judaism as a responsibility.

Judaism is life. It’s the best “social life” a Jew can have—not entertainment, but a living identity.

Children can sense when a father does mitzvot resentfully, like a burden. That attitude doesn’t hold. But when children see joy, pride, and love in Torah life, it becomes something they want to belong to.

And Rav Mansour added one crucial warning: never put down another Jew—especially in front of children. The cost is enormous.

Rabbi Yaniv Meirov is the CEO of Chazaq and Rav of Congregation Charm Circle in Kew Gardens Hills. Since 2006, he has helped thousands of Jews reconnect with their faith through community events, lectures, and public school outreach, earning recognition from gedolim, elected officials, and community leaders for its impactful work. As Chazaq Torah Talks recently aired its 214th episode with Manny Behar, Rabbi Meirov continues to bring thoughtful, heartfelt conversations to the Jewish world—bridging tradition with today’s challenges, one episode at a time. The Rav can be reached for comment at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Building Communities That Build People

Typography

- Smaller Small Medium Big Bigger

- Default Helvetica Segoe Georgia Times

- Reading Mode