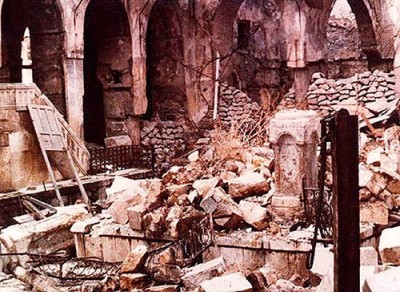

Seventy years ago, a week before Hanukkah, on 18 Kislev, a disaster befell Syrian Aleppo Jews. Three days after the United Nation voted to partition Palestine into a Jewish state and an Arab state, on December 2, 1947, riots broke out in Aleppo and other Syrian Jewish communities. Arson, looting, destruction, and burning of synagogues and Jewish-owned businesses took place. They still refer to that date as laylat il haraq, Arabic for “the night of burning.”

Aleppo, the city where I was born, is in northern Syria, and one of the oldest continuously-inhabited cities in the world. Legend has it that Avraham Avinu stopped there to milk his goats and offer it to travelers on his way to the Holy Land from Ur Kasdim. Thus, the city’s Arabic and Hebrew name is “Halab,” meaning milk. In Jewish writings, Aleppo is identified with Aram Soba, mentioned in the book of Samuel II Ch. 8 (and in Psalm 60) as being conquered by King David’s general, Yoav Ben Seruya. Tradition has it that he laid out the foundation of the Great Synagogue, also referred to by the Aleppo Jewish community as the Yoav Ben Seruya synagogue. The Great Synagogue was the repository of the Aleppo Codex, Keter Aram Soba, (“The Crown of Aleppo”). The Codex is considered the most authoritative and likely the earliest surviving document to preserve our mesorah on the vocalization, pronunciation, punctuation, and trop of the Bible. The codex was written in the 10th century CE in Tiberias and was used by Maimonides himself in his studies. One of his descendents brought it to Aleppo in the 14th century. While part of it, from Beresheet to KiTavo, is missing, the remainder is housed in the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, after being smuggled out of Aleppo in the 1950s (see Matti Friedman’s book, The Aleppo Codex).

During the Ottoman Empire, Aleppo’s Jewish population peaked at around 13,000, including Mizrahi (people whose mother tongue was Arabic or Farsi), and Sepharadim (refugees after the expulsion from Spain in 1492.) Jews were mostly left by the Turkish authorities to run their community, but had to submit to Muslim laws in criminal cases. Following World War I and the defeat of the Ottoman Empire, Syria became a French mandate and gained its independence in 1946. After that date, and as the certainty of the rebirth of Israel became imminent, many Jews saw the handwriting on the wall, and began to leave Syria.

My grandfather, Harav Abraham Yaakov Dweck Hacohen, was a descendent of a family of rabbis. His father, Yaakov Shaoul Dweck Hacohen, was at one time the Av bet din (head of the Jewish tribunal) of the Aleppo Jewish community and the author of the books Sheerit Yaakov (The Remnant of Jacob) and “Derekh Emunah (The Path to Faith). Rav Abraham left Aleppo for America, entrusting the Torah scrolls of his own synagogue to another.

On that horrible night 70 years ago, the rioters destroyed and torched many synagogues and torah scrolls. Until recently, when the community in Aleppo was still active, Chai Kislev was commemorated as a day of fasting. My own parents had left Aleppo, just ahead of Syria’s independence in 1946, to Beirut, Lebanon, where I was raised. Lebanon was considered a safer country, where the Maronite Christians at the time were deemed the majority, and held the presidency of the country. We immediately registered at the American consulate, awaiting our turn at legal immigration, and in 1956, we came to America. To be eligible to come to the America, we had to have a guarantor to assure the government that we would not go on welfare for at least five years. That was the law.

Many early Syrian Jewish immigrants from Aleppo had settled in Brooklyn. For the Jews remaining in Aleppo after Syria’s independence, life became intolerable, especially so after the establishment of Medinat Yisrael. The Jews of Aleppo were subjected to harassment and lost the right to hold property, travel, or engage in free commerce. Those caught attempting to flee Syria were dealt with harshly. Some still managed to escape. It wasn’t until the early 1990s, under heavy American pressure, that Syrian dictator Hafez el-Assad allowed the remaining thousands to depart as “tourists,” i.e. taking only what they could carry. They must not be found to have gone to Israel. Many of those refugees came to Brooklyn, and were welcomed by the Aleppo Jews already there. They were given material, financial, psychological, and spiritual help. One newcomer told one my aunts, “When I left Aleppo, I kept the house keys on the front door; I didn’t want them to break the door when they come to loot.”

Today, the newcomers are fully integrated in the Syrian Jewish community, and lead a modern Orthodox lifestyle. Syrian Jews are proud that almost all their children attend yeshivot. They were joined by Jews from Lebanon (many originally Syrian, in fact), when Lebanon, enmeshed in its own civil wars, became hostile to Jews, with several kidnapping and murder of Jewish community leaders. The remaining Jews of Lebanon went to Israel when Israeli forces invaded Beirut in 1983. Today, only a handful of Jews remain in Syria and Lebanon.

In December 2015, Mayor Bill de Blasio spoke on Shabbat at Shaare Zion, the largest Syrian Jewish synagogue of Brooklyn. According to the New York Post, he “implored a skeptical congregation … to empathize with Muslim refugees from their shared homeland and welcome them to New York. Orthodox worshippers at Brooklyn’s Congregation Shaare Zion murmured uncomfortably as de Blasio compared Syrian refugees fleeing their war-torn country with Jews fleeing the Nazis.”

To many Syrian Jews, the present destruction of Aleppo seems a validation that the sins of the fathers are visited on their children: “avon avot al banim” (Exodus 20:5). Although their fear of Syrian authorities is gone, many Aleppo Jews have not forgotten 18 Kislev, lelat il haraq. “In these days of retrenchment of the Mizrahi communities, it might be worth to commemorate this event, if only so we not forget the horrors that visited us on the 18 of Kislev.»

Isaac Sasson lives in Flushing. He is a retired scientist, a community leader, and a philanthropist.

The Night Of Burning In Aleppo

Typography

- Smaller Small Medium Big Bigger

- Default Helvetica Segoe Georgia Times

- Reading Mode